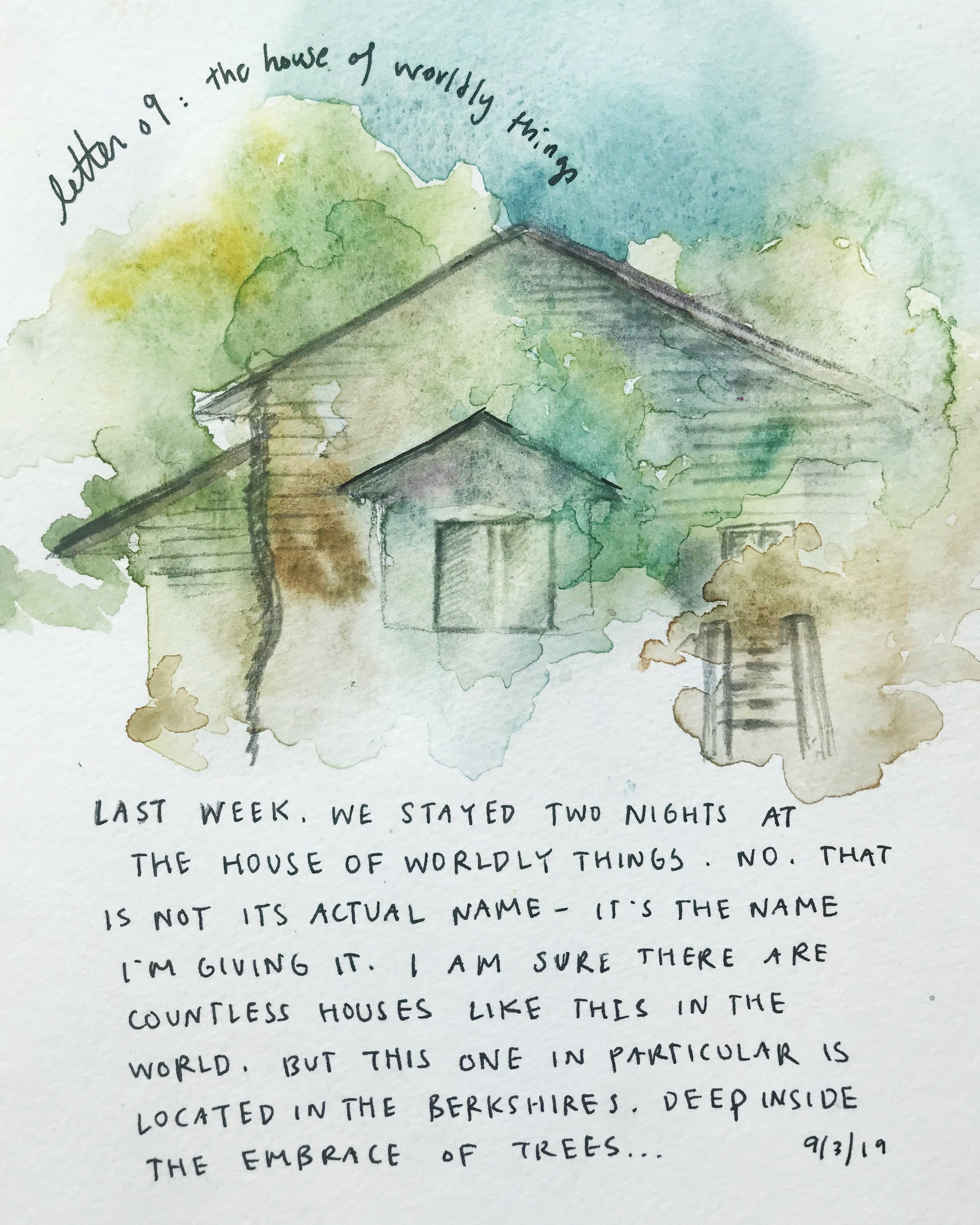

the house of worldly things

dear friends,

last week we stayed two nights at the house of worldly things. no, that is not its actual name — it is the name I’m giving it. I am sure there are countless houses like this in the world, but this one in particular is located in the Berkshires, deep inside the embrace of trees, where, in order to get there, you must leave a paved road and drive for at least ten minutes with the sound of rocks and twigs crushing under your wheels. it’s an expansive house built from dark wood, with equal parts of it bathed in light and shadow.

when you arrive, the house will be empty. your host says he will be in a nearb y town doing “tree work.” but there will be music playing from a large yoga studio room — electronic instrumental, psychedelic fusion sounds — and you will not know whether to keep it on, or to turn it off. at the entry to the living room, there will be a wooden stand with a massive dictionary-encyclopedia flipped to the name of a country, like Burma or Madagascar, and its pages will look very old. you will find an atlas of vintage maps. Japanese travel periodicals. a record player. a chess set. a glass cabinet of books (fiction, your host says, nonfiction is upstairs). and on the center of the kitchen island, illuminated by skylight, a large, carved wooden tray that you will stare at — trying to decipher whether or not it is used for some pagan ritual — before you realize that it is just a cheeseboard.

when you first meet the man who owns this house of worldly things, he will greet you with a hug and a kiss on the cheek. just from his embrace, you can feel that he is a consciousness awakening man, an earth loving man, a man with stories to tell, most likely a vegetarian. he will tell you that he is fifty nine and a half, nearly sixty years old, but he looks forty, and dare I say it, he is hot. or maybe his energy is hot. or maybe, somewhere in his infinite kitchen shelves of exotic spices and mason jars of dried herbs you’ve only remotely heard of, he has made the concoction for eternal youth.

you didn’t ask him about it, but you do ask him how he came upon this house of worldly things, how he filled it. he will tell you that he’s a writer and human rights investigator, and has traveled to fifty seven countries. he does work around genocide, in war torn countries, and now he does tree work. eight months ago, he sold his family farm that they’ve owned for two hundred and fifty years, and barely bought this house — from an elderly woman who was desperate, in debt, and wished to move to India.

that night, he will walk you through the basement and show you how to use the infrared sauna and the wooden sauna he’s building on the bedrock of the house. you will feel very impressed. you will ask him, point blank, whether he lives here alone, and what his plans are for such a grand place.

if I’m being completely honest, he says, I fell in love with a woman.

she was going to move in here with me, but a month ago, she said she needed her freedom, and disappeared. I’m hoping to fall in love again with a woman who will live here with me. I’m in a good mood right now, he says, because I was in a tree all day. but this morning, I woke up with terror.

he says all of this in passing, and then he says he’s going to bed, and asks you to please turn off the living room lights before you go to sleep.

it will take you ten minutes to locate, test, and turn off all the lights. it is the kind of house that has little lights for every nook, and an infinite abundance of light switches. that night, you will read his travel essay on Afghanistan from a periodical on his coffee table, finger through his copy of the Tao De Ching, and begin a companion book of meditations to Henry Thoreau’s Walden. in the opening pages of this book, you see a handwritten note addressed to him that reads: *may this house manifest all your dreams. *

you wished you could have said something to him. you wished that you had a chance to respond to his words with more than just a look. you wanted to meet his eyes and say: *I understand.* I know this terror you speak of. I know this darkness. I know how the house of your dreams can turn, and feel suddenly like emptiness; how the void eats you from within, a parasite of loneliness. I know this feeling, and I am sorry you are in pain.

the next morning, you will sit under the cool shadow and finish reading the book about Walden, cover to cover. during the rest of your stay, you will use his kitchen, cut vegetables with his knives, season them with his spices, listen to his vinyl records, sit outside in sunlight on his back porch, flip through more of his vast collection of books, but you will see him only briefly. he will float in and out, exchanging a few words, before going on a camping trip.

then the second morning will come, and you will drive away again, down the long dirt road, back into the world of light and rustling trees, away from the house of worldly things, and slowly, through traffic, back into the city of cities.

it will occur to you that you could travel the world three times over, collect treasures from every country, fill your mind with knowledge, culture, wisdom, and experiences, buy a magical old house to put it all in, invite any and all guests to join you there, and yet, still, decades later, what you crave most will remain the same, will be still so simple.

a love to set your heart down for. to breathe a sigh of relief. a love that could hold all fragments of you with tenderness and care, soften the edges of your darkness, illuminate the walls of your being, make your house feel like a home.

is it too much to ask? is it a delusion of dependency?

is it better, instead, to give this kind of love and belonging to yourself, instead of seeking it in another human being? or maybe one comes first.

sometimes, I don’t know. I am trying to answer this question, and maybe I will tell you about it in a few years, after I have journeyed the world myself and amassed my own collection of worldly things, and shared it all, in words, with you.

.

.

.

.

.